Hey there, everyone!

This week has been a little crazy for me. In addition to my thesis work, I just started taking two summer classes, one of which is charmingly entitled Physics for Future Presidents. I’ve been trying to stay ahead of my new classwork, and keep to my proposed schedule with my thesis materials. Luckily, I’ve been able to spend time working with some of the other Dietrich Scholars – Lucy Pei and Kaylyn Kim – to help keep myself focused.

This is Kaylyn. You should go take a look at her project! When you’re done reading my blog post, that is.

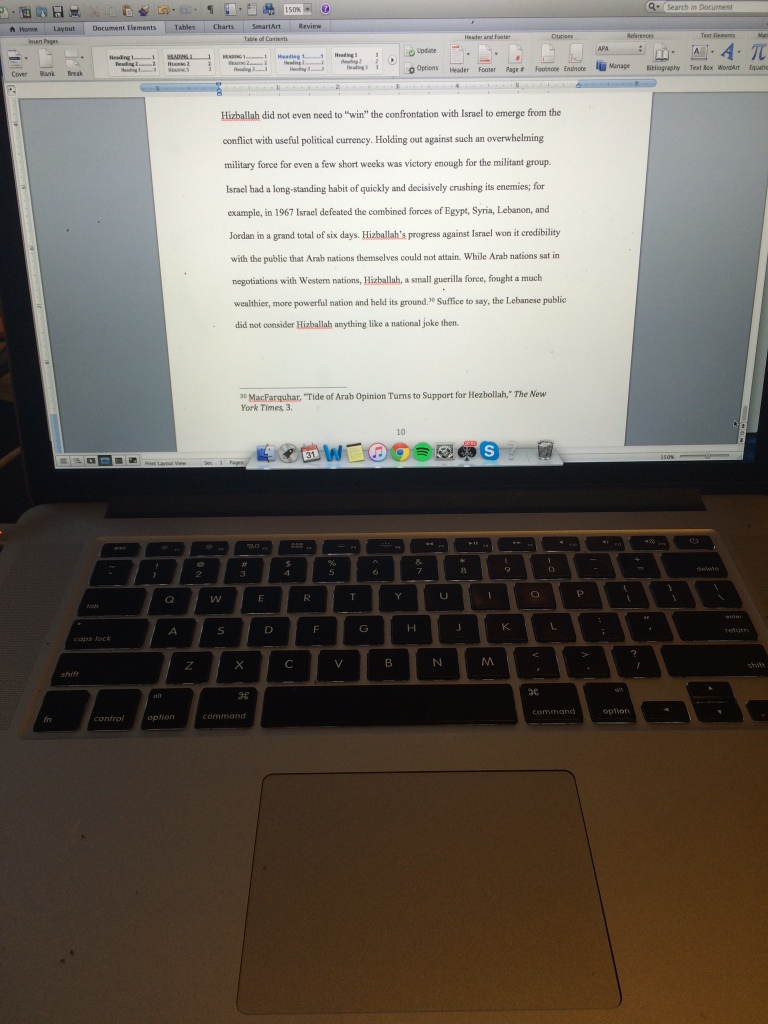

This week I started digging my teeth into my IRA sources, and changing tact in this manner has been enormously helpful. When I was only looking at Hezbollah sources, it could be difficult for me to determine which organizational aspects were important, and which ideological threads would be comparable between the two wildly different groups. One of the trends that caught at my attention was the idea of conferring and obtaining legitimacy when one is attempting to lead a militant organization.

With that in mind, let’s talk about the word “craic.”

“Craic,” usually used with the definite article, is a uniquely Irish term for news and gossip, entertainment and fun. “What’s the craic?” is basically a colloquial Irish version of: “What’s up?” The word is actually based on the early English word crack, which was used in England in the same context in the late 1800s. However, as the term died out in England but remained prominent in Ireland, people started spelling it as if it were an Irish word.

(Bear in mind, I learned all this in a tour of Dublin when I was studying abroad last semester.)

Wherever it comes from, “the craic” is now a very uniquely Irish concept. It’s even on T-shirts.

(This is my Dublin souvenir t-shirt. The craic was indeed mighty.)

While putting a word on a t-shirt doesn’t necessarily indicate a wider cultural trend, I did hear the word when I was in Dublin, and even if it’s more of a tourist gimmick, the combination of English-Irish heritage of the word is really interesting. It’s English in origin and even in its traditional spelling, but now doesn’t even exist there anymore.

For groups like the IRA, legitimacy is of paramount importance. One of their basic justifications for their existence is the idea that the British government imposed partition upon the people of Ireland, and given that that separation between the north and south of Ireland was both imposed by a foreign government and undesired by the Irish, that makes that action doubly invalid. In the IRA’s own eyes, they represent the true will of the Irish people.

All this makes me think that legitimacy is a tricky topic. Having English roots doesn’t make craic any less Irish. While I don’t think that the IRA represented the will of the Irish people as a whole, they absolutely represented grievances that many Irish people felt quite strongly. Both of these instances make me wonder how and why legitimacy gets conferred. How did the term craic survive in Ireland while fading away in the land of its birth? How does a group know – or argue, I suppose – that it represents the true will of an entire nation?

One of the profoundly fascinating things about non-state actors is that they can change and challenge the way we think about non-state actors. We often assume (Western) states are legitimate because they’re simply there. We don’t necessarily think about if they should have the power they do, and if so, why. Legitimacy doesn’t simply emerge from some governmental void; it must be created, and then continually considered and discussed. It must be regarded, to some degree, as the construct that it is.

Learn more about my project.

When she applied for the fellowship program, Thompson wasn’t exactly sure what she wanted to do her thesis on, but she knew that it would involve non-state groups and political actors. She settled on Hezbollah, Arabic for “Party of God,” and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) because they’re two non-state actors that have separate but active militant and political arms.

When she applied for the fellowship program, Thompson wasn’t exactly sure what she wanted to do her thesis on, but she knew that it would involve non-state groups and political actors. She settled on Hezbollah, Arabic for “Party of God,” and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) because they’re two non-state actors that have separate but active militant and political arms.

You must be logged in to post a comment.